“The problem is so well-defined, so neatly packaged, with both causes and cures known, that if we don't eliminate this social crime, our society deserves all the disasters that have been forecast for it.” René Dubos on Lead Poisoning, 1969

In Murderland, Caroline Fraser does what most scientists won’t: she draws a straight line from widespread lead poisoning to the mid-20th-century spike in serial murders. It’s a bold move. Proving that a toxic metal triggered a crime wave is like trying to pin a murder on a smudge of a fingerprint.

But Fraser’s argument isn’t just grim speculation—though she clearly has an eye for the morbid. Some people collect stamps. She collects crime scenes.

Given the years she grew up in, her obsession makes sense. The late ’60s and early ’70s were a fever dream of violence: bombings, assassinations, kidnappings, mass shootings. JFK, RFK, MLK. Patty Hearst. The Zodiac. The Manson Family. Death was in the air—and not just metaphorically. It came with the exhaust fumes, paint flakes, and smelter stacks.

The link between lead and violence isn’t new. In 1943, Boston pediatrician Randolph Byers and psychologist Elizabeth Lord studied 20 children who’d been hospitalized with “mild” lead poisoning. “Mild” only because they weren’t in a coma. But they weren’t fine. They struggled in school, set fires, acted out. One stabbed a peer in the face with a fork. Only one graduated from high school.

That was 80 years ago. We should’ve learned. We didn’t.

Widespread Poisoning, Urban Collapse

Fraser writes, “The scale of environmental devastation caused by the industrialization of WWII exceeds anything the planet has ever seen.” She’s not exaggerating. Cities like Baltimore, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Tacoma were drenched in lead—from gasoline, paint, plumbing, and smelters. It wasn’t just brains that got scrambled. It was neighborhoods, schools, entire communities.

Lead didn’t just stunt IQs or trigger tantrums—it reshaped personalities. A study linking atmospheric lead to personality traits in 1.5 million people across the U.S. and Europe found that kids exposed to more lead grew into adults who were less agreeable, less conscientious, and more neurotic. In short, lead dissolved the social glue: trust, responsibility, emotional stability.

Children born after the phaseout of leaded gasoline—thanks to the 1970 Clean Air Act—showed healthier personalities. The same trends appeared in Europe. If you wanted to sabotage a city’s ability to function, lead was the perfect weapon.

Add redlining, highway-driven displacement, and racist housing policy, and lead poisoning didn’t just hollow out cities. It helped blow them apart.

The Crime Surge Nobody Blamed on Lead

In the ’70s and ’80s, violent crime surged. Taylor noted that the number of serial killers climbed steadily—from 55 in 1940 to 72 in 1950, 217 in 1960, 605 in 1970, and 768 by 1980. Politicians blamed crack, rap lyrics, welfare mothers, and “super-predators.” Almost no one blamed lead.

But the evidence was hiding in plain sight.

Criminologist Deborah Denno, using the Collaborative Perinatal Project, scrutinized dozens of possible early-life risk factors for crime. One kept flashing red: lead. “It totally blew me away,” she said. The kids most heavily exposed to lead were the ones most likely to commit violent crimes—homicide, rape, assault.

And she wasn’t alone.

From Bone Lead to Bullet Wounds

In 2002, Dr. Herbert Needleman—a pioneer in lead research—went straight to the bone. Literally. He and his team measured bone lead levels in 194 teens who had been adjudicated for criminal behavior and compared them to 146 non-delinquent controls. The results? The adjudicated youth had significantly higher bone lead levels. It wasn’t subtle. Lead had left its mark—not just in their records, but in their skeletons.

Studies from the U.S. and New Zealand paint the same picture: early lead exposure—whether measured in blood or shed baby teeth—increased the risk of aggression, impulsivity, and arrests in young adults.

The risk persists even at the lower levels of lead poisoning still found in cities today. In Milwaukee, public health researchers found that youth with early childhood blood lead levels above 50 parts per billion were twice as likely to be involved in gun violence. They estimated that lead exposure accounted for more than half of the city’s firearm-related offenses.

This wasn’t a fluke. Cities with the highest rates of lead poisoning—Milwaukee, St. Louis, Detroit, Chicago—also had the highest rates of violent crime.

Call it poor impulse control or conduct disorder if you like. But let’s be honest: it wasn’t just broken windows. It was broken wiring.

Serial Killers and Smelters

Epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose taught that small shifts in a population’s average can have big effects. Raise the average blood pressure, and more people have strokes. Raise the average level of aggression or impair impulse control, and you don’t just get more fights—you get more violent crimes. Maybe even serial murders.

Do we have bone lead data from serial killers? No. But if we did, I’d bet it would back Fraser’s hunch.

Some scientists will scoff: “You can’t prove causation with observational studies.” But that’s how we nailed smoking as the cause of lung cancer. Others say many kids with high lead exposure turn out fine. True. But the weight of evidence says lead boosts the odds of violence, especially when paired with trauma, stress, or genetic vulnerability.

We can’t ethically dose kids with lead for research. But we let the lead industry do it—without consent, in the name of progress and profit. In the lab, golden hamsters dosed with lead became aggressive and unpredictable, attacking their cage mates without warning.

Lead didn’t just irritate them. It rewired their brains.

The Decline in Crime (and Lead)

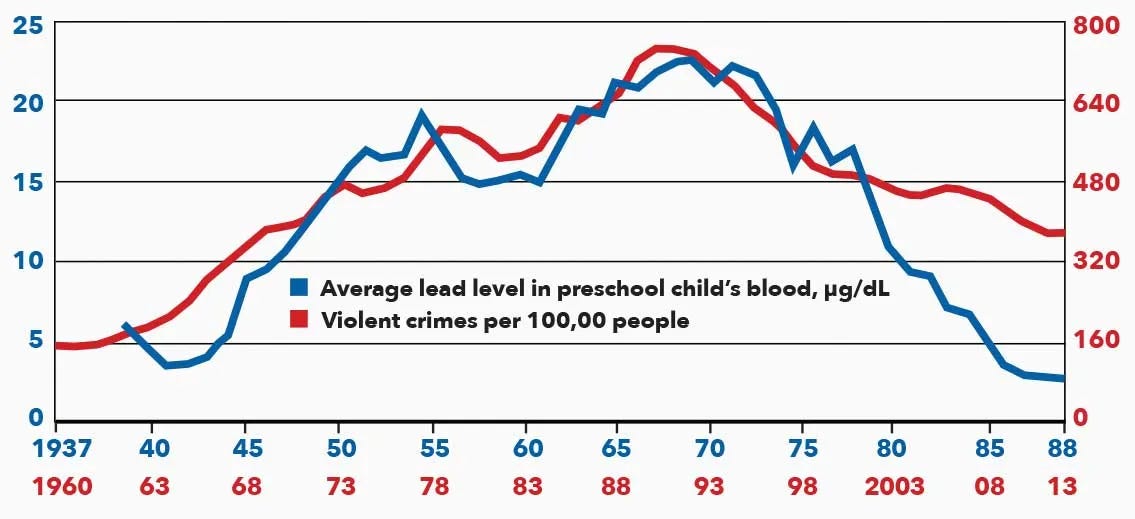

Economist Rick Nevin looked at crime rates alongside historical lead exposure. He found a 23-year lag between average blood lead levels and violent crimes—just long enough for poisoned kids to grow up. The curves fit like puzzle pieces.

Average Blood Lead Levels and Violent Crimes, US (Nevin, 2000)

Violent crime began to fall in the early 1990s. Maybe it was Roe v. Wade, smarter policing, or the end of the crack epidemic. Or maybe it was unleaded gas. Giuliani and Bratton took credit, but the drop began before Rudy took office—and kept going long after he left.

Nevin also found a haunting echo: incarceration rates fell 30% for men in their 20s, but rose 86% for those in their 40s and 50s. The leaded generation was aging into prison.

Molecules, Morals, and Missed Warnings

We accept that Ritalin and Prozac can alter behavior. But the idea that molecules from smokestacks or plumbing could do the same? That’s where people draw the line. That’s not science—it’s selective skepticism.

Lead doesn’t explain all violence. Guns matter. So do poverty, trauma, racism, and bad policy. But blaming “bad apples” while ignoring a poisoned orchard is willful denial.

Our regulatory system wasn’t built to protect the public. It was built to promote commerce. Once a chemical gets the green light, reversing course takes a mountain of evidence—and a public outcry. That mountain is buried in junk science, delay tactics, and industry-funded doubt.

In 2024—100 years after the U.S. was first warned by scientists not to add tetraethyl lead to gasoline—EPA scientists concluded that lead likely causes criminal behavior.

The real crime isn’t what lead-exposed children grew up to do. It’s what we let industry do to them, decade after decade, even after we knew better.

This report is simply outstanding. When industry added lead to gasoline, it already knew that children were dying from environmental lead paint poisoning. They admitted as much in a paper published by doctors in Boston (McChan and Vogt) and from internal corporate documents. Lanphear shows that putting the burden of proof on the public to prove harm, instead of requiring industry to prove safety before unleashing an environmental poison, is a crime against children and ends up contributing to our decline as a civilization.

Thank you. Perfect timing for a post I am working on.