Gerontogens at the Gate

Industrial Chemicals and the Case for an Environmental Theory of Aging

Chronic disease didn’t overtake humanity overnight—it crept in on a tide of silent inflammation. One leading lens on that tide is inflammaging: the idea that aging is driven, and often accelerated, by a slow-burn rise in pro-inflammatory signals like IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP. Once dismissed as biological background noise, these cytokines—text messages of the immune system—now look like a unifying force behind heart disease, diabetes, dementia, and frailty.

Track the cytokine curve across a lifespan and the modern epidemic of chronic illness comes into view. Inflammaging isn’t just a theory of biological wear-and-tear—it’s a roadmap to why our later years have become a high-risk zone for disease, and a guide to where prevention might begin.

A 2025 study by Franck and colleagues in Nature Aging measured cytokines in older adults in industrialized Italy and Singapore and compared them to adults in two small-scale societies: the Tsimane of the Bolivian Amazon and the Orang Asli of Malaysia. In the industrialized settings, pro-inflammatory markers rose steeply with age. Among the Tsimane and Orang Asli, those markers stayed flat. Elders in their seventies had cytokine profiles more typical of people in their thirties.

The message is clear: inflammaging is not inevitable. It is conditional. It depends on how—and where—we live.

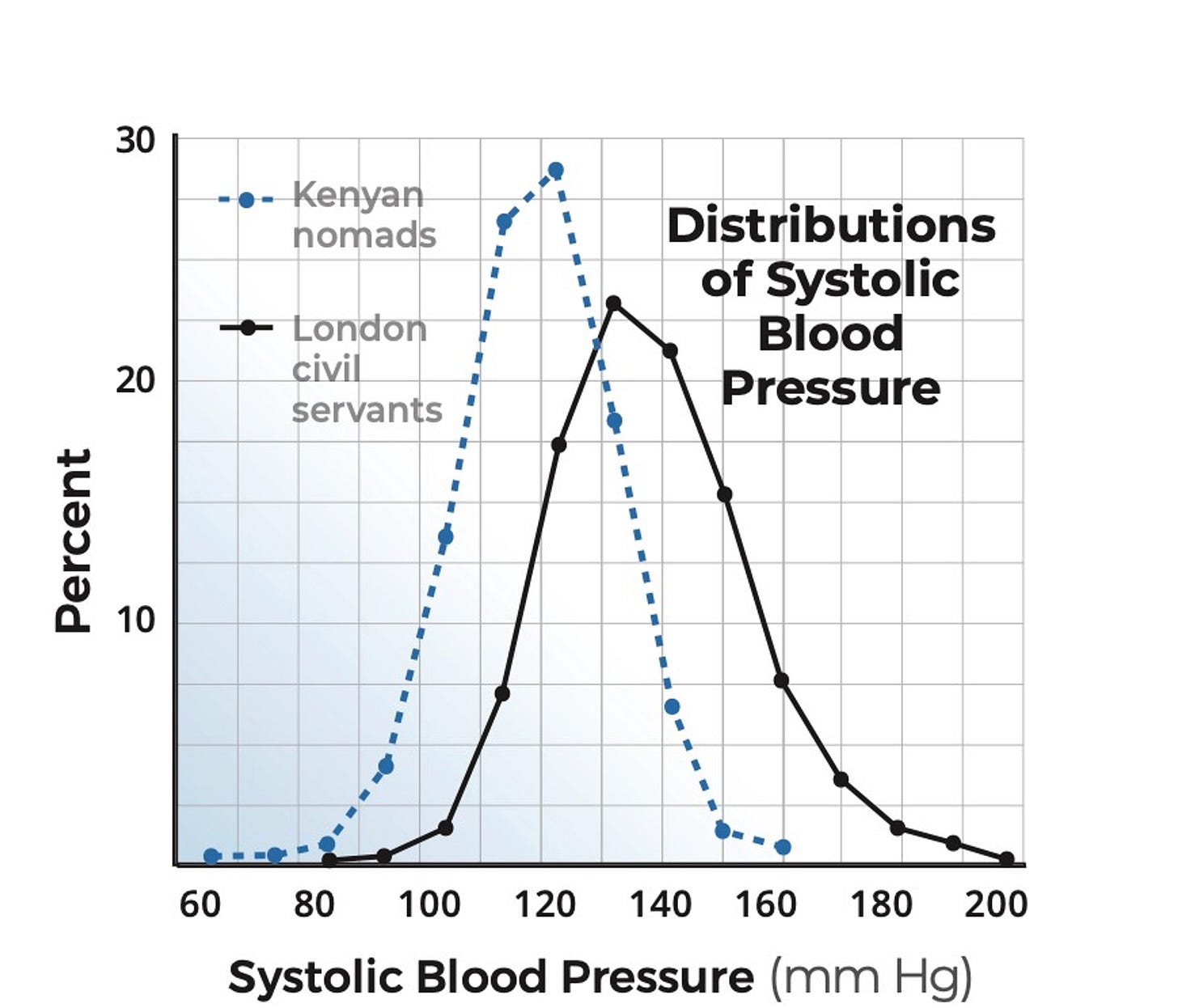

The finding echoes older work in cardiovascular epidemiology. Traditional societies rarely develop hypertension. Among the Tsimane, systolic blood pressure rises by barely one millimeter per decade. Nearly 50 years earlier, Geoffrey Rose documented the same pattern when comparing London civil servants to Kenyan nomads: the British blood pressure curves rose steadily with age; the Kenyan curves stayed flat.

Diet and physical activity explain part of this gap. But mounting evidence points to something more insidious: gerontogens—industrial chemicals like lead, cadmium, arsenic, phthalates, PFAS, and fine particulate air pollution. These agents induce oxidative stress, damage DNA, alter immune signaling, and accelerate the very cellular processes that define aging.

As early as 1987, geneticist George Martin proposed the term gerontogens for any environmental factor that "accelerates, mimics, or exaggerates the biological effects normally associated with aging." (It’s a mouthful, but think of the word teratogens.) Martin saw aging not just as a product of time and biology, but as a process shaped—and sped up—by environmental insult. His definition included radiation, metals, and even chronic hyperglycemia. The central idea still holds: environmental agents that hasten cellular damage effectively compress the timeline of aging, turning late-life pathology into midlife disease.

While inflammaging is a key pathway, it’s only one of many ways aging is accelerated. Toxic chemicals don’t just inflame the immune system—they damage DNA, impair mitochondria, disrupt hormones, and alter gene expression. Cadmium shortens telomeres and phthalates diminish testosterone. PFAS, the forever chemicals, weaken immune response and PM₂.₅ impairs mitochondrial function. A new U.S. study using nationally representative data found that cadmium, lead, and tobacco smoke were strongly linked to faster aging based on epigenetic clocks. Accelerated aging isn’t just about inflammation—it’s a network of disrupted systems wearing down resilience.

Building on this concept, Annette Peters and colleagues recently outlined eight hallmarks of environmental insults that contribute to chronic disease and accelerated aging: oxidative stress and inflammation, genomic alterations and mutations, epigenetic changes, mitochondrial dysfunction, endocrine disruption, altered intercellular communication, changes in the microbiome, and nervous system dysfunction. These closely mirror the nine hallmarks of aging identified in biogerontology. The overlap is no accident. What’s new is the mounting evidence that industrial pollutants strike all these systems.

These findings support a broader conclusion: aging itself is shaped by environment. What we breathe, drink, and absorb into our bodies helps determine how fast our biological clocks tick—regardless of what our calendars say.

And yet, our policy response remains sluggish. Too many public health agencies treat toxic chemicals as niche concerns, rather than systemic drivers of disease and disability. The science linking lead to cardiovascular deaths, PFAS to immune suppression, and PM₂.₅ to accelerated aging is solid. But regulatory action is still slow, fragmented, and easily derailed by industry lobbying and manufactured doubt.

This is the hidden scandal of modern aging: we celebrate the cellular complexity of aging biology while ignoring the pollutants that warp it. We invest billions in precision medicine, CRISPR, and senolytics while failing to phase out lead pipes or clean up air pollution.

An environmental theory of aging would rest on three premises:

Chronic inflammation and accelerated biological aging are acquired, not inevitable.

Multiple industrial chemicals act as gerontogens, accelerating core aging pathways.

The most effective, equitable anti-aging strategy is to reduce population-wide exposures to these toxic chemicals and pollutants.

Cellular interventions still matter, but they will always chase damage we could have prevented upstream.

Franck’s study reminds us that biology is shaped by context. The low-inflammation profiles of Orang Asli elders aren’t due to superior genes—they reflect fewer industrial exposures. Yet even as we marvel at the Tsimane’s stable blood pressure, we allow leaded aviation fuel to rain down on our own communities.

The real breakthrough isn’t a pill or a protein—it’s a paradigm shift. We must recognize that reducing toxic exposures is preventive gerontology. It’s not just environmental policy—it’s how we slow the aging process for everyone.

If forest dwellers can reach old age without inflamed arteries or roaring cytokines, industrial societies can too. But only if we stop feeding the flames.

So how have you found it, for yourself/family adhering to a regimen like this? I presume it takes a fair amount of effort/research on a regular basis? Lacking a govt that is willing to thoughtfully address these issues alas.