The Long Poisoning

When Regulatory Delay becomes State-Sanctioned Suffering

Meet Illinois farmer Ron Niebruegge. At 55, he was convinced the doctors had it wrong. He had always been sturdy and active—trail-riding his horses, taking his wife dancing. But the strange stiffness in his left arm, the dizzy spell, the unexpected fall—all carried the same grim message: Parkinson’s disease. Now, at 70, he can barely make it across a room without falling. The horses are gone; the dancing shoes put away.

Ron is not an outlier. Parkinson’s is now the fastest-growing neurological disorder in the world, and scientists have repeatedly linked a pesticide—paraquat—to the disease. While paraquat has been banned in Canada and the European Union, it remains widely used across the United States. Despite mounting evidence, it is still permitted—and increasingly used—in the U.S.

If we want to understand the price of regulatory delay, we need only look at lives like Ron’s—and then widen the frame. For every farmer with Parkinson’s, there are children waiting months or years for autism evaluations, young adults facing a surge of early-onset cancers, and countless families grieving heart attacks, infertility, kidney disease, and other chronic conditions rooted in long-ignored environmental exposures.

This is the real ledger of delay: a multigenerational tally of suffering caused not by fate or genetics alone but by known or suspected toxic chemicals released into our air, water, food, and bodies long before they were ever proven safe.

When is a Death a Murder?

It’s a provocative question—one that makes many people uncomfortable—but it sits at the heart of our public-health crisis. When a corporation markets or emits a chemical it knows to be harmful, conceals evidence of its toxicity, and delays regulation for decades, what do we call the resulting deaths? Accidents? Tragedies? Externalities?

Or something closer to collateral damage—losses quietly absorbed by families, communities, and entire generations so that the gears of the economy can keep turning.

We rarely use words like violence or harm for environmental exposures, because their effects are slow and unseen. But many chronic diseases of the modern era—lung cancer, heart attacks, premature births—trace back to deliberate choices to release chemicals long before their safety was established. These are not random biological flukes. They are slow-moving disasters driven by corporate decisions—and tolerated by the systems meant to protect us.

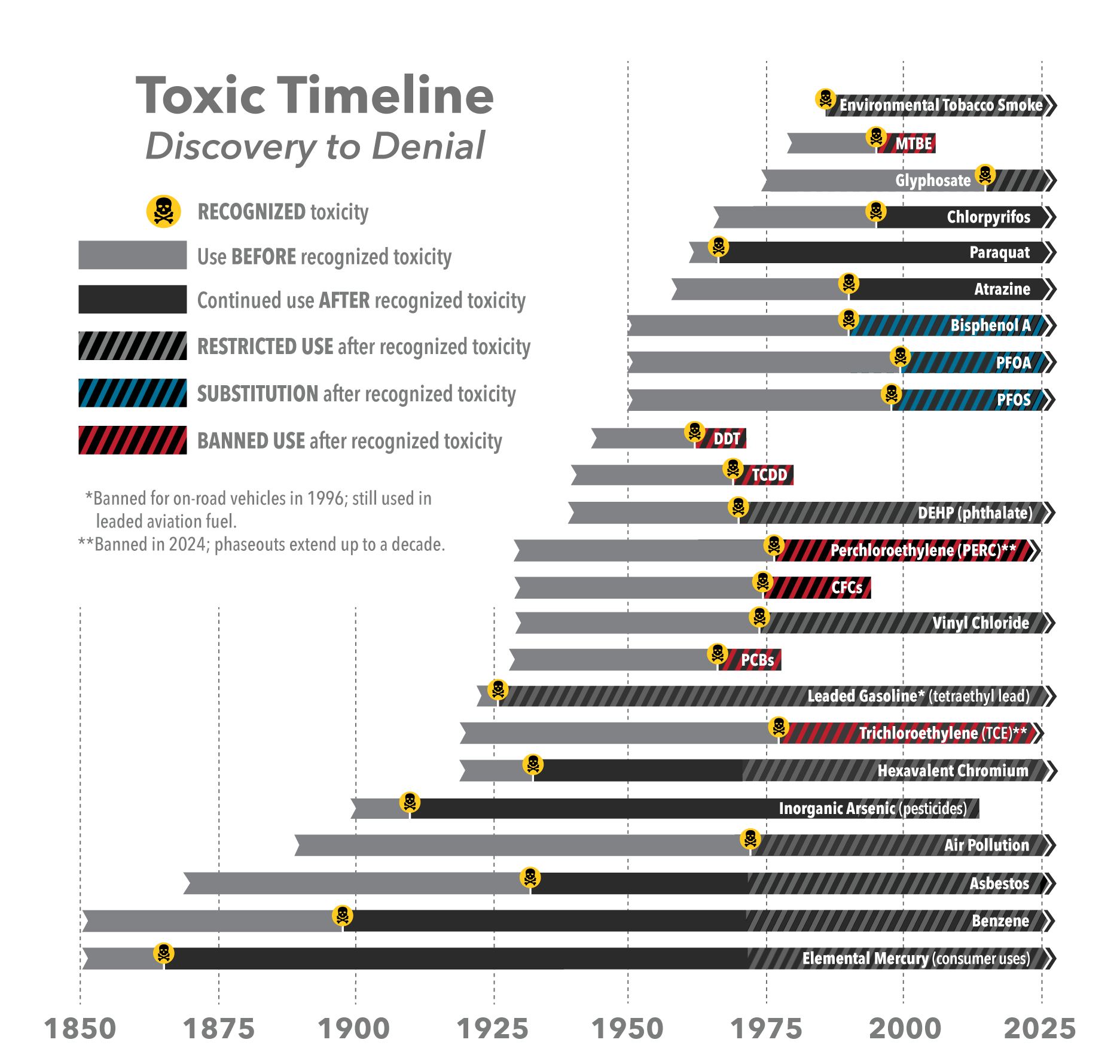

The European Environment Agency captured this pattern in its landmark 2013 report Late Lessons from Early Warnings. Across hundreds of pages, they documented a century of delayed recognition and regulatory failure—from asbestos to benzene, PCBs to DES, leaded gasoline to ozone-destroying CFCs. The same sequence repeats with numbing predictability: an early warning emerges, industry dismisses or buries it, and regulators—outmatched, under-resourced, or politically constrained—wait years or decades to act. When protections finally arrive, the harm is baked into the population.

This is the anatomy of delay: a system designed to look careful while quietly authorizing decades of unnecessary harm.

Across these cases alone, regulatory delay has cost millions—perhaps billions—of lives. These “late lessons” are not historical footnotes; they are state-sanctioned deaths—the predictable, measurable result of policies that privilege economic convenience over human life. They are not historical footnotes or technical oversights. They form a pattern of generational harm in which governments, fully informed by early warnings, allowed corporations to continue practices that are killing millions of people year after year.

When a state knowingly permits exposures that it understands will cause cancer, brain injury, and early death, the line between negligence and complicity blurs. What we call “late lessons” are, in truth, the record of how nations allowed slow-motion mass casualties to accumulate in plain sight.

And despite everything we’ve learned, the collateral damage continues. We are already living through a quiet pandemic of environmentally driven disease—fueled by toxic metals, pollutants, and plastics that power modern industrial life. These exposures rarely cause dramatic poisonings. Instead, they harm us through repetition: a cell injured here, an immune pathway disrupted there, a hormonal signal nudged just enough to alter development or aging.

The modern wave of chronic disease reflects the slow unraveling of the molecular infrastructure of life.

Every family I know has a story:

a child born prematurely

a niece with leukemia

a parent lost early to a heart attack

a sister with lung cancer

an uncle with Parkinson’s

a grandparent with dementia

We treat these as genetic defects or private misfortunes. They are not. They are public failures—the predictable result of a regulatory system built to protect the short-term economy, not human health.

This system rests on a flawed assumption: that most chemicals have “safe thresholds.” Yet for many of the best-studied toxicants—including lead, air pollution, benzene, asbestos, and tobacco smoke—the science shows no safe level. Carcinogens and other toxic chemicals do not politely stop causing harm at the point where regulation finds it convenient.

Despite decades of evidence, only a small number of chemicals have ever been truly banned in the United States. Most—including known carcinogens and other toxic chemicals—remain legal, managed through exposure limits rather than eliminated. Leaded gasoline, asbestos, forever chemicals, and benzene were restricted only after overwhelming harm became impossible to ignore, often decades after early warnings. This is not a failure of science. It is a failure of governance—a regulatory system designed to tolerate harm until it becomes undeniable, rather than prevent it when the evidence first appears.

And here is the deeper truth: every death from regulatory delay is a preventable death. Every chronic illness from long-ignored exposures is a form of societal negligence.

The burden is not distributed equally. It falls on children before they are born. On workers in refineries, smelters, nail salons, and industrial farms. On communities downstream and downwind. On the poor, who are easiest to overlook. And on all of us, navigating a daily soup of low-dose toxicants without informed consent.

Preparing for What Comes Next

We cannot afford another century of early warnings followed by late action. Preparing for the next wave of environmentally induced disease means:

Thoroughly testing chemicals before they reach the market or are emitted from smokestacks—not decades later.

Regulating entire classes of chemicals, not chasing them one by one.

Strengthening independent science and national surveillance for biomarkers of environmental chemicals.

Accelerating the development of safer alternatives and green chemistry.

Reducing exposures using the same logic applied to infectious disease: prevention at the population level.

Modern public health began when societies stopped blaming individuals and started cleaning up water, sanitation, air, and housing. The same principles will save us again.

When Should Corporations Be Held Responsible?

Returning to the opening question—when is a death a murder?—the better question may be this: When do repeated, preventable harms become corporate crimes?

If a company markets a product knowing it can cause disease or death, misleads regulators, suppresses evidence, and profits while the public pays the price, accountability should not be optional.

We hold individuals responsible for a single reckless act. Why not corporations for decades of reckless policy? Relying on the courts isn’t enough. By the time the legal system responds, the damage is irreversible—the illnesses diagnosed and the bodies already counted.

Late lessons are no longer acceptable. Collateral damage is no longer inevitable. The science is clear, the costs enormous, and the moral calculus unmistakable.

If we want a healthier future, we must build a regulatory system that holds corporations responsible before the damage is done—not after.

I wanted to share a comment John Ancy sent me after reading this essay. It meant a great deal to me, especially because John—a brilliant physiologist and respiratory therapist—is not someone who gives out compliments lightly. (He’s also my brother-in-law.) John wrote: "I enjoy your substack articles, passionate, insightful and well documented. While in graduate school in 1973-75, I worked at St. John's as an RT, mostly in ICU. I remember one horrific Saturday evening shift. More than a dozen young people were brought to the hospital in acute respiratory failure. Many required mechanical ventilation and several succumbed to ARDS. They all had been at a party smoking BRIGHT green Marijuana that had a "peculiar" taste. Reportedly, the pot was tainted with paraquat. Apparently, the DEA was assisting Mexico with paraquat based eradication program. It killed the plants but left the leaves in a beautiful green state. Perfect for sales purposes and lethal. And it is still available. Wow."

I am with CDN club of Rome & I doubt there will be significant enough changes to stop the misery.. until the pain is so obvious that something will be done.... but too little too late... your point that this is a kind of murder really strikes me as the correct pt of view, and it applies to all environmental crimes like you described