Gardiner Harris’s new book, No More Tears, reads like a thriller—if thrillers came with footnotes and pathology reports. It tells the story of how one of America’s most trusted brands, Johnson & Johnson, knowingly sold talcum powder contaminated with asbestos—a known carcinogen—while manipulating science, gaming regulations, and polishing its wholesome image. It’s a familiar script: delay, deny, discredit.

And if it feels like déjà vu, that’s because we’ve seen this movie before.

The First Casualty

Asbestos was once celebrated as a miracle material: fireproof, flexible, durable. It lined ships, brake pads, floor tiles, and attic insulation. But it came with a catch—you could spin it like wool, inhale it like dust, and die from it.

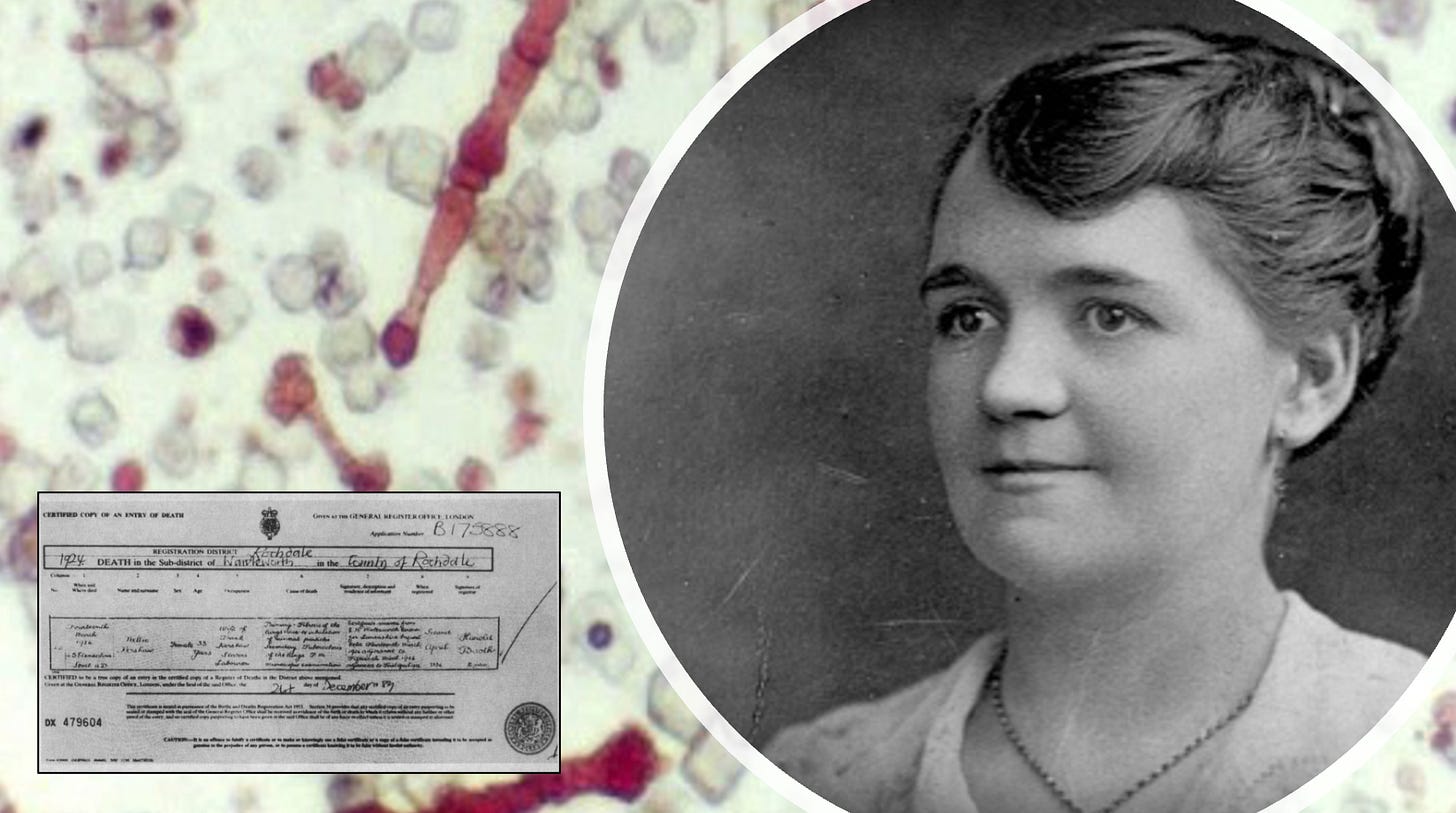

The first documented victim was Nellie Kershaw, a 19th-century textile worker in Manchester. She spent her days breathing in asbestos fibers—indestructible shards that burrowed deep into her lungs. Her breathing worsened. Her health collapsed. Her employer shrugged.

After she died, no formal inquest was held. But there was Dr. William Cooke, who performed an autopsy and found her lungs riddled with lesions—and fibers identical to those floating in the factory air. He didn’t coin the term asbestosis, but he helped give it shape.

Selikoff vs. the System

Enter Irving Selikoff. The son of Jewish immigrants, he was turned away from U.S. medical schools, so he trained in chest medicine at a TB sanatorium—a job most physicians avoided for fear of infection. Maybe it was that outsider status that helped him see what others overlooked.

In 1953, Selikoff opened a clinic in Paterson, New Jersey, near an asbestos plant. Workers kept showing up sick—from fibrosis, lung cancer, and something rare and sinister: mesothelioma. Selikoff asked the company for records. They refused.

So he turned to the union. With support from the Heat and Frost Insulators, he launched a landmark study. Among 632 workers, 45 had died of lung cancer—nearly seven times the expected rate. Mesothelioma? Almost exclusively seen in asbestos-exposed workers.

But what about smoking? In a follow-up study, Selikoff showed that the real killer combo was asbestos plus cigarettes. The risk wasn’t additive—it was multiplicative. If you smoked and worked with asbestos, your odds of lung cancer skyrocketed.

Selikoff didn’t just publish. He testified. He organized. He warned anyone who would listen. He tried to work with industry. Industry fought back. He was blackballed from the National Academy of Sciences and painted as an alarmist. In hindsight, he was just ahead of the curve—and he was right.

The Science of Doubt

In the 1970s, some researchers began arguing that chrysotile asbestos (the curly kind) wasn’t as dangerous as amphibole types (the straight, needle-like kind). A 2001 Science News article, "No Meeting of the Minds on Asbestos," chronicled the growing divide. Some said chrysotile was safe if left alone. Others pointed to the mounting body count.

It wasn’t just miners and factory workers. In Libby, Montana, a town blanketed by asbestos-contaminated vermiculite, miners, families, and schoolkids all got sick. No one warned them. No one cleaned it up—for decades.

Household Exposure: The Powder Problem

One study suggested that half of all New Yorkers had asbestos in their lungs. Selikoff was especially troubled by what he found in housewives.

In 1968, when Arthur Langer, a mineralogist at Mount Sinai, ran baby powders under an electron microscope, the culprit came into focus: asbestos—sharp, needle-like fibers—in products marketed for infants.

This wasn’t abstract. In 1982, Dr. Daniel Cramer published a study in Cancer showing that women who used talc-based powders in the genital area had nearly double the risk of ovarian cancer. The powder, often contaminated with asbestos, migrated up the reproductive tract and triggered inflammation—a known cancer risk.

More than 30 studies followed. A 2008 meta-analysis found a 33% increased risk of ovarian cancer among long-term talc users. Every year, Johnson & Johnson’s baby powder contributes to an estimated 2,500 ovarian cancer cases in American women. About 1,500 die.

The science was clear enough for courtrooms. But not, apparently, for regulators.

Why the FDA Failed

So why didn’t the FDA step in?

Cosmetics aren’t pre-approved. Baby powder, unlike drugs, didn’t need to prove safety before hitting shelves.

The FDA couldn’t mandate recalls. Even with evidence of contamination, the agency could only ask nicely.

No asbestos testing standard existed. Companies used outdated methods that intentionally overlooked asbestos fibers. Modern microscopy wasn’t required.

Industry data ruled. Johnson & Johnson ran its own tests—and sometimes didn’t share the results.

Regulatory capture did the rest. A 1994 petition to require asbestos testing went nowhere. Not until 2020—after lawsuits and media pressure—did the FDA begin using better tests.

The FDA wasn’t asleep. It was underpowered, underfunded, and outmaneuvered.

The Comforting Illusion

What’s damning about Johnson & Johnson isn’t just that it sold a tainted product—it’s that it sold trust. Baby powder wasn’t just talc. It was branding: soft, white, pure. They marketed comfort. They delivered cancer.

Company memos from the 1950s show they knew the risk. But instead of reformulating—something competitors managed—they chose a different tactic: sow doubt. Fund friendly research. Attack critics. Hide behind regulatory gray zones.

If this all sounds familiar, that’s because it is. It’s the same playbook used by Big Tobacco. The Lead Industry. Exxon. Monsanto. Asbestos wasn’t just the first industrial killer. It was the earliest corporate cover-ups to be beta-tested on the public.

Ghost Exposures

Some mesothelioma patients never worked a day in a factory. They never handled insulation. And yet the fibers still found their way in—through air, through products, through baby powder.

No known exposure? That’s not an excuse—it’s the evidence. Asbestos was everywhere.

The Legacy of Selikoff

In 1982, Selikoff and Italian physician Cesare Maltoni—himself a whistleblower on vinyl chloride—founded the Collegium Ramazzini, an international academy devoted to protecting workers and the environment from industrial hazards.

Selikoff died in 1992. He had no children, but he left behind a scientific family: scientists like Barry Castleman, Arthur Frank, Phil Landrigan, and Richard Lemen, who continue to warn the world—often with little applause.

OSHA recognized its danger in 1971. The EPA tried to ban it in the '80s. The courts overturned that ban in 1991, calling it too burdensome. And yet, the U.S. only prohibited ongoing uses of chrysotile asbestos in 2024.

Canada waited until 2018—after decades of subsidizing asbestos exports to developing nations, all under the pretense that it was "being used responsibly." Regulatory theater. Deadly consequences.

Meanwhile, people keep dying. Mesothelioma takes 20 to 40 years to appear. The victims showing up today were exposed when Reagan was in office.

Regulation Isn’t the Enemy

We’re often told regulation is the problem. Too slow. Too clunky. Too bureaucratic.

But if this story teaches us anything, it’s that what some call red tape is really a safety net. Without watchdogs, we get wolves in the nursery.

Agencies like the FDA need more than authority. They need teeth. Independence. Scientific integrity. Otherwise, we’re just letting companies self-regulate—which, history shows, is like asking the fox to write the henhouse rules.

What We Owe the Dead

Nellie Kershaw died without compensation. Since 1990, five million people have died from asbestos-related disease. Another 200,000 die each year. Many never knew what was killing them.

We owe them more than sympathy. We owe them action.

Irving Selikoff liked to say, “Science is necessary but not sufficient”. We need a system that doesn’t let corporations’ profit from poison while hiding behind corrupted science and regulatory paralysis. Because somewhere out there, the next “magic mineral” is already being marketed. And the next cover-up is already underway.

The only question is: will we stop it in time?

Warren Zevon’s farewell song after he found he was diagnosed with mesothelioma, a universally fatal disease.

Kevin: Thank you. I remember Zevon's song, Keep Me in Your Heart, but I didn't know he wrote it after being diagnosed with mesothelioma. I embedded Zevon's video in the post. Asbestos is pervasive.

Excellent, excellent post. Bruce, each piece is more powerful than the last. You may have been trained as a scientist, but you're also an excellent historian.